Somewhere in the mid-70’s when I was working at the

Century 21 Theatre on Colorado Blvd. as an usher, I established the weekly

habit of getting off my night shift, taking my paycheck to Safeway to cash and

then going to Peaches records on Downing and Evans before they closed at

midnight and perusing their cut-out bins. Filled with mysterious, colorful

covers, I really learned how to explore music there. It’s where I turned myself

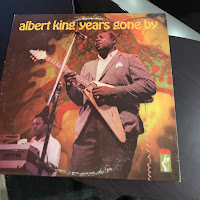

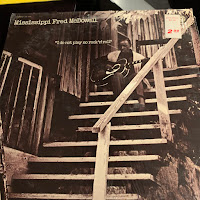

on to Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Gene Autry, Lefty Frizzell,

Professor Longhair, Gatemouth Brown, John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins. The

cutout bins were the final resting place for the cast-off legacy of our own

cultural highpoints. The radio was filled with Journey and REO Speedwagon, and

I was finding myself drawn to Burl Ives and Champion Jack Dupree. The cut-out

bins were a refuge from the modern world and a doorway to the secret history of

an American life completely different than the one I knew. Once I stepped

through, I never fully came back through that doorway. I found myself more

comfortable in the past. The things I heard there changed everything I heard in

the present. Every guitar player had to stand up to Blind Blake, every

songwriter had to match Jimmie Rodgers, and every legend be as mysterious as

Robert Johnson; obviously, an impossibility. But here in the cut-out bins, I

could lose myself in big black vinyl slabs of another era.

Around this same time I got my first electric

guitar. I got a few instruction books, and a few friends showed me a couple of

things, but my real course of study was to listen to B.B. King records and try

to copy his playing. In spite of how simple it sounded, I found it was very

hard to sound like he did. When I got to see him live, I realized how much of

his sound was connected to the vibrato he created with his left hand, as well

as the overwhelming physicality he put into every moment of his performance. I

was obsessed with the mystery of the blues and dove into the deep end.

Of course, the deep end is the pre-war period of

blues captured largely on 78 rpm records. I quickly realized that a) these

original records were rare as shit, and I couldn’t afford them, and b) the

cutout bins were filled with reissues of the early stuff and c) some of the

original guys and many of the great post-war guys were actually still alive and

available to see at clubs and festivals. I started building a relationship with

the genre and the people who shaped it. I bought a lot of records by blues rock bands like Led Zeppelin, Cream, ZZ Top and Hendrix which all ended up pointing me to the source. Slowly I built a collection and started understanding the different sub-genres and stylistic variations of the blues.

After I got Twist And Shout and the CD reissue

market took off, the massive body of rare recordings from the 20’s and 30’s started

to become available and affordable. I continued to get original LPS and even a

few 78’s where I could, but I remain grateful for the access labels like JSP,

Document, Shanachie and Yazoo provided me to the Blues on CD. At some point in the 90’s we were selling music at

a blues festival in the Golden Triangle. Our tent ended up being next to the

tent of a man named Dick Waterman, a fascinating nut and world-class

photographer who had helped rediscover a number of lost bluesmen in the 1960’s and

then documented them with a rare and insightful eye. I befriended Dick and

ended up buying a bunch of his beautiful photographs.

Three events in the early 2000’s helped keep my

love alive. The first was release of the documentary Desperate Man Blues

about 78 rpm collector Joe Bussard, a true curmudgeon and laser-focused

aesthetician, which brought into focus my own beliefs about music before the

age of mass media. Regionalism is what makes different kinds of music special.

There are forces at play nowadays that make music an entirely different thing.

Next was getting my 1946 Seeburg 78 RPM jukebox.

With this restored beauty in

my life I had a vehicle worthy of taking those rare 78s out for a drive.

Finally, it was the purchase of a large collection of 78s I did a few years

ago. The records were amazing - all rare blues, gospel and r&b from the

20’s through the early 60’s. The only problem was they were soaked in urine and

many of them were scratched beyond play. Still, I embarked upon cleaning and

salvaging as many as I could. There were many surprises and lots of classic

blues. About half way through the collection I got to the end of a stack and

there it was staring back at me.

The Masked Marvel (Charley Patton) "Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues" an

incredibly rare 78 from 1929. With trembling hands I placed it on the

turntable. It was so scratched, it sounded like Charley Patton was singing on

Mars. But just the act of holding the record and letting the 80-year old

grooves unwind in my presence was a moment of intense clarity for me. I

realized how important the blues have been in my development as a music

enthusiast, collector and retailer. Few things protect me from the effects of

modern malaise more than the protection of The Masked Marvel.

- Paul Epstein