Think about the

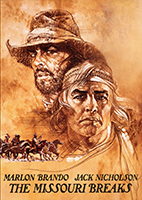

extraordinary turn Marlon Brando’s career was taking in the 1970’s. After stalling a bit in the late 60’s he

came roaring back in 1972 - jowly, greying at the temple and more potent than

ever in The Godfather and Last Tango In Paris. Two braver explorations of middle age could

not be imagined, then… silence, until 1976 when he returned – greyer still, jowlier

yet, but no less intense and seeming to have tapped into some sort of cosmic

awareness that made him a real-life cross between con-man, genius, artist,

shaman and fool. It was also impossible to take your eyes off of him in what

could be considered his last great role of substance in The Missouri Breaks (I

love Apocalypse Now, but it is hard to call what Brando

did in it as “substantive.” Memorable yes, substantive maybe less so.). Director Arthur Penn created a stylish western

in the classic mode, which is elevated to something truly memorable by Marlon

Brando’s inexplicable performance. From the moment he appears on screen as

Robert E. Lee Clayton he is magnetic - both compelling and terrifying at the

same time. He is a regulator (a legal

assassin) who has been brought from Wyoming to Montana to help rancher David

Braxton (John McLiam) and his attractive daughter Jane (Kathleen Lloyd) deal

with a band of horse rustlers (Jack Nicholson, Harry Dean Stanton, Randy Quaid

and more) who have been causing trouble. Brando enters the action as an exotic

swashbuckler; fringed leather jacket, long hair and an Irish accent. He

immediately shows himself as a man not to be trifled with, appraising Nicholson

as the thief and beginning to exact punishment on the gang. His speed and

deadly accuracy prove his reputation as an uncontrollable, but ultimately successful

executioner.

Think about the

extraordinary turn Marlon Brando’s career was taking in the 1970’s. After stalling a bit in the late 60’s he

came roaring back in 1972 - jowly, greying at the temple and more potent than

ever in The Godfather and Last Tango In Paris. Two braver explorations of middle age could

not be imagined, then… silence, until 1976 when he returned – greyer still, jowlier

yet, but no less intense and seeming to have tapped into some sort of cosmic

awareness that made him a real-life cross between con-man, genius, artist,

shaman and fool. It was also impossible to take your eyes off of him in what

could be considered his last great role of substance in The Missouri Breaks (I

love Apocalypse Now, but it is hard to call what Brando

did in it as “substantive.” Memorable yes, substantive maybe less so.). Director Arthur Penn created a stylish western

in the classic mode, which is elevated to something truly memorable by Marlon

Brando’s inexplicable performance. From the moment he appears on screen as

Robert E. Lee Clayton he is magnetic - both compelling and terrifying at the

same time. He is a regulator (a legal

assassin) who has been brought from Wyoming to Montana to help rancher David

Braxton (John McLiam) and his attractive daughter Jane (Kathleen Lloyd) deal

with a band of horse rustlers (Jack Nicholson, Harry Dean Stanton, Randy Quaid

and more) who have been causing trouble. Brando enters the action as an exotic

swashbuckler; fringed leather jacket, long hair and an Irish accent. He

immediately shows himself as a man not to be trifled with, appraising Nicholson

as the thief and beginning to exact punishment on the gang. His speed and

deadly accuracy prove his reputation as an uncontrollable, but ultimately successful

executioner. With the central

conflict established, Penn goes about turning the movie into a philosophical

treatise on the difference between being a thief and a killer, and if either of

those is morally worse than being a bad person on the right side of the law. David

Braxton, it turns out, is a world-class creep who deserves whatever he gets,

while Nicholson seems to be a more three-dimensional man than his designation

as horse rustler might indicate. He yearns for the honest life - or at least

the love of a woman who has lived the honest life - available in the person of

Braxton’s daughter. Brando’s character Clayton appears more and more like a

scorched earth psychopath, hell-bent on destroying his prey as violently as

possible, letting no one - including those who hired him - stand in the way.

His inhumanity grows with each scene as Nicholson becomes an increasingly

sympathetic protagonist. As Clayton’s killings take on greater cruelty with

each victim, Clayton’s personality takes on more complexity. He begins shifting

accents from Irish to Southern, to female (complete with unforgettable drag costume) and back to Irish. His performance is always on the edge of

hallucinatory, the cutting edge of menace and hilarity. In spite of it being

one of his least famous movies, I believe The

Missouri Breaks contains one of Brando’s most beguiling performances. By

the end of the movie, he is a truly frightening presence - unpredictable,

deadly and unstoppable - beyond the control of laws or bullets. The shocking

twist at the end remains a great cinematic trick, never failing to surprise.

With the central

conflict established, Penn goes about turning the movie into a philosophical

treatise on the difference between being a thief and a killer, and if either of

those is morally worse than being a bad person on the right side of the law. David

Braxton, it turns out, is a world-class creep who deserves whatever he gets,

while Nicholson seems to be a more three-dimensional man than his designation

as horse rustler might indicate. He yearns for the honest life - or at least

the love of a woman who has lived the honest life - available in the person of

Braxton’s daughter. Brando’s character Clayton appears more and more like a

scorched earth psychopath, hell-bent on destroying his prey as violently as

possible, letting no one - including those who hired him - stand in the way.

His inhumanity grows with each scene as Nicholson becomes an increasingly

sympathetic protagonist. As Clayton’s killings take on greater cruelty with

each victim, Clayton’s personality takes on more complexity. He begins shifting

accents from Irish to Southern, to female (complete with unforgettable drag costume) and back to Irish. His performance is always on the edge of

hallucinatory, the cutting edge of menace and hilarity. In spite of it being

one of his least famous movies, I believe The

Missouri Breaks contains one of Brando’s most beguiling performances. By

the end of the movie, he is a truly frightening presence - unpredictable,

deadly and unstoppable - beyond the control of laws or bullets. The shocking

twist at the end remains a great cinematic trick, never failing to surprise. In

the 34 years that have passed since I last saw this movie, I had forgotten

almost everything about it. So the panoramic cinematography, realistic take on

the Old West setting, excellent music and funny dialogue were all a welcome

re-acquaintance. It is Marlon Brando’s terrifying depiction which I had not

forgotten, and it was, in fact, even more potent than I remembered. He has had

one of the most terminally appraised careers in the history of film, yet his

depiction of Robert E. Lee Clayton does much to justify his genius reputation.

In

the 34 years that have passed since I last saw this movie, I had forgotten

almost everything about it. So the panoramic cinematography, realistic take on

the Old West setting, excellent music and funny dialogue were all a welcome

re-acquaintance. It is Marlon Brando’s terrifying depiction which I had not

forgotten, and it was, in fact, even more potent than I remembered. He has had

one of the most terminally appraised careers in the history of film, yet his

depiction of Robert E. Lee Clayton does much to justify his genius reputation.

-

Paul

Epstein

1 comment:

Holy Cow Paulie! That's a mighty well-said mouthful there! Great movie. I love it.

Post a Comment