Early 20th Century recordings can sound

faint and frail to 21st Century ears, like it’s made by paper dolls in a

cardboard box or something, so on first listen the hundred or so songs that

Gertrude “Ma” Rainey recorded over the course of four years in the 1920s might

give the impression of a woman who is small and thin. But she was a mountain of

a woman who dominated every room she ever sang in, from cramped juke joints to

cavernous opera houses. And she was a superstar at a time when being a

superstar must’ve really meant something because America was living it up,

blissfully unaware of the Great Depression lurking around the corner. What’s

more, she was a black superstar at a

time when the Ku Klux Klan were at the apex of their power and most black women

would’ve been happy just to be considered human, much less an American idol.

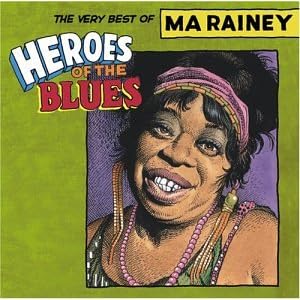

Rainey wasn’t afraid to flaunt it either. She wore brightly colored silks and

boas and necklaces made out of diamonds and solid gold coins, and gold capped

the teeth in her broad smile. Her live shows were legendary, often beginning

with her singing inside of a giant Victrola from which she’d emerge festooned

with ostrich feathers, her jewelry shimmering under the stage lights, her skin

made up to look like glittery gold.

I recently moved

to the Southern city Rainey called home and bought a house just a few blocks

from her home, which has been turned into a museum. It’s in what used to be the

black business district but is now surrounded by shotgun shacks, empty lots,

AME churches and a big housing project. The house stands two stories high, by

far the biggest in the area, and her queen-sized tigerwood bed and her piano

are on the first floor, right where they were when she was host of the

hoppingest house in town; black touring musicians and entertainers would often

stay with her because they weren’t allowed to stay at nearby hotels. There are

a few pictures of her on the walls, but only a few, because that’s all she ever

allowed to be taken of her. She thought of herself as ugly, an opinion most

others seemed to share with her, even her own bandmates: Gatemouth Moore, who

toured with her for a number of years, has been quoted as saying, “She wasn’t a good lookin’ woman. I won’t

call her ugly, but what a terrible face!” Still, she had a lot of sex appeal;

she’s said to have had a lot of lovers, many of them women. You can feel that

allure in her music. It’s early blues with a full jazz band treatment - smoky

and sultry. In fact, hers are the earliest black blues recordings we have. She

was the first to ever record the song that Elvis opened his concerts with,

known in her time as “See See Rider Blues.” She’s often called the “Mother of

the Blues” because she was the first to put her voice to record, in 1923. By

that time, she’d already been playing the minstrel and Vaudeville circuit for

more than 20 years, and the white record execs went into the venture with

skepticism because she was believed to be on the decline. But her records sold

like crazy and she almost single-handedly broke open a market for “race

records,” 78s of black artists marketed mainly to black audiences. Her band was

the launching pad for a stunning list of artists, including Coleman Hawkins,

Louis Armstrong and “the Father of Black Gospel Music,” Thomas Dorsey.

There are a lot

of CD collections of Ma Rainey recordings, and all of them are wonderful. Yes,

the recording value is awful, and you can often hear the scratches on the old

shellac they were recorded from. But for me they began to sound magnificent

after I toured her house and learned more about her -- learned, for instance,

that when she began her career as a teenager at the turn-of-the-century

microphones and PA systems weren’t readily available, so she made a star of

herself by filling huge rooms with the sound of her captivating voice and her

commanding presence. Or that the way these recordings were made was by her

standing in front of her full band and belting it out into a great big cone.

Knowing these things, her music suggests the rarest of artists, the sort of

genius whose talents and skills seem to lie outside the realm of human ability.

The more closely I listen, the more I hear subtlety and artistry in her voice. Same

thing with the band. There are moments where they verge on the psychedelic,

especially when they throw in a bit of trumpet wah-wah, or kazoo, or a saw,

which sounds exactly like a theremin, very sci-fi and weird. These songs might

sound meek and reedy by today’s hi-fi standards, but in fact they’re

monumental, and huge enough to be heard and felt all the way across a century.

No comments:

Post a Comment