Within

my first two years of being in business I got two big introductions to Blue

Note records. The first came when a guy named Bob came into the store. I

immediately recognized him as a guy who used to work at Kingbee records on

Evans near D.U. He then went on to work at Record Revival (later Jazz Record

Revival) on Broadway. He was always a nice guy and had recommended a few albums

to me over the years that I really liked. This day he was selling a handful of

CDs. He pointed one out to me. “You ever heard this one?” He shook his hand

like he was putting out a match. “Hot Stuff.” The CD was Cornbread by

Lee Morgan. I took it home that night and played it. It was indeed a

magnificent jazz album. Morgan had such a strong tone and melodic sense on

trumpet, his band was red hot and the recording was really present and snapped

with the tight arrangements.

Within

my first two years of being in business I got two big introductions to Blue

Note records. The first came when a guy named Bob came into the store. I

immediately recognized him as a guy who used to work at Kingbee records on

Evans near D.U. He then went on to work at Record Revival (later Jazz Record

Revival) on Broadway. He was always a nice guy and had recommended a few albums

to me over the years that I really liked. This day he was selling a handful of

CDs. He pointed one out to me. “You ever heard this one?” He shook his hand

like he was putting out a match. “Hot Stuff.” The CD was Cornbread by

Lee Morgan. I took it home that night and played it. It was indeed a

magnificent jazz album. Morgan had such a strong tone and melodic sense on

trumpet, his band was red hot and the recording was really present and snapped

with the tight arrangements.

The

second event came when someone dropped a stack of free magazines at the store.

It was a guide to independent record stores nationally. I thumbed through it

and was surprised to see our store in there. I’ll never forget it. They said we

were a good store with a lot of nice used stuff. Then the author explained how

he had gotten a couple of rare Blue Note pressings for way less than they were

worth out of our racks. I was stung. Not by the loss of revenue, but at the

perceived lack of knowledge. It changed the way I approached my job. I thought,

if I’m going to do this, I have to know at least as much as the average customer

(a ridiculous thought-there is no average customer). It gave me a kick in the ass to both really

learn about label variations and to understand better what the mystique was

with Blue Note.

It

took a few years before we got to the point that we were buying large

collections every day, but it did finally happen, and I started to see some

Blue Notes come through the door. A regular character who bought a lot of jazz

named Shelby passed away and his family sold his records and he had a handful

of great titles. They were beat to shit, but I decided to take a couple home

and try them out. I will never forget the sense of

revelation I had when I put that first original Blue Note pressing on my

turntable and the exciting sound recording mastery thundered out of the

speakers. I had never heard a record sound so alive! And remember this record

looked like hell. Once the needle fell into those grooves, the scuffs and grime

disappeared and, like magic, it sounded like you were in the studio with a room

full of great players. I would learn this was no fluke. Blue Note records were

largely recorded by a man named Rudy Van Gelder in his home in New Jersey. A

dentist by trade, he loved jazz and sound, and he combined those two passions

to create an undying legacy. The first generation or two of Blue Note are

unparalleled recordings. Van Gelder’s abilities, the musicians, the times, and

the pressing technology-I’m not sure exactly what all the factors were, but

nothing sounds like a Blue Note.

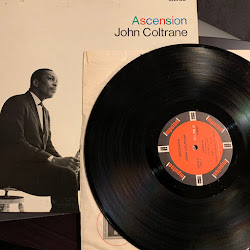

A

number of Blue Note recordings became some of my favorite albums. One in

particular blew my mind. Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music is an incredible mix of

jazz, funk, gospel and conscious soul unlike anything else. It is cosmic and

earthy at the same time. It’s one of the records I’ve tried to turn people on

to over the years. Finally, an original mono copy of Lee Morgan’s Cornbread came

in to the store. I couldn’t believe it. I was so excited. I took it home that

night and breathlessly put it on the box. I wish I had the words to convey exactly

how amazing that first listen was. From the opening notes of Larry Ridley’s

bass and that first blast of horns from Lee, Jackie McLean and Hank Mobley I

couldn’t believe how present the music was. You could literally feel the room

the album was recorded in. You could see where each player was in your mind’s

eye. This was why I was collecting records. This exact feeling of presence-like

you were there. I have played that record, I’ll bet, a thousand times. When

people come over and want me to show off my stereo or collection, the night

will always include Cornbread, usually with me holding the record up and

saying “this is why we are still in business!” And I believe that. The specific

magic contained in a well-pressed piece of vinyl is something that can not be

undervalued. It is the medium through which the magic of music can best be

expressed (short of live performance). After the many, many playings, Cornbread

has lost none of that magic. The record still sounds amazing-no surface

noise, just the pulse-quickening greatness of the original session. It is my

go-to audiophile recording. Nothing sounds better to me.

The

magic and mystery of Blue Note is well known in the collecting world. They are

rare as hen’s teeth and highly sought after. Thus, the prices have become very

“dear” as it were. Even so, if you see a nice one, and if you are excited by

the art and science of recording, as well as great jazz-there is no more

rewarding investment to be had in the record collecting world.

Here are some of my favorites.