-Paul Epstein

Showing posts with label Miles Davis. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Miles Davis. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

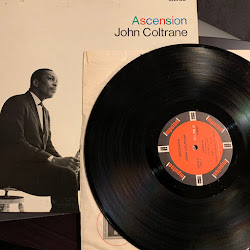

Trane

My main things in terms of collecting live concerts and

endless variations of the same song are improv and soloing. When it comes to

studio albums it’s songwriting, performance and recording. However, there is no

end to the number of versions of a given song I can listen to if the band involved

can improvise meaningfully and the individuals can solo interestingly. In Jazz,

the king daddy for me is John Coltrane. He proved himself a great player,

arranger and soloist early in his career-especially during his time with Miles

Davis’ groundbreaking band, but in the mid-60’s, his LPs on Impulse records

contain THE most incendiary soloing and the headiest improvisation in modern

jazz. I remember the first time I brought 1966’s Ascension home, it

scared me to death. Trane’s ferocious soloing, able to drill down to hell or

scream heavenward in 2 bars while his incredible band-including Archie Shepp,

Pharoah Sanders, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones on this album was

right with him, the blood pressure to his heartbeat-many of them equally

impressive soloists. I was terrified and thrilled to hear someone screaming

through their instrument this way. I had heard Hendrix and other rockers do it,

but it was often in a pretty conventional setting. Trane was reaching new

space-finding music that had never been heard or even thought of before. The

only way I can describe it, is when Coltrane is in full blow mode, I feel the

need to be alone with the music-loud. It’s not music you can easily share with

others. Like really dirty comedy records, you feel the need to close the door,

roll up the windows and listen without judgement. Trane has plenty of more

easily digested music, but the string of albums from about 62 until his death

in 67 are unparalleled in their cosmic intensity. The search for original

copies of most of Trane’s albums obsessed me for many years. I’ve got a bunch

now, and they are some of my most prized LPs. Dig!

Monday, October 15, 2018

I'd Love to Turn You On #216 - Dexter Gordon - Go!

Dexter

Gordon’s 1962 Blue Note record Go! is

the kind of record that you can give to your friends who say they don’t

understand jazz and they will love it. Like Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, or Song for My Father by Horace Silver it crosses genre lines and

rises into classic territory. It has an energy and a quality to it that make it

special. It features Dexter Gordon on the saxophone, Billy Higgins on the

drums, Sonny Clark on piano, and Butch Warren on bass.

Dexter

Gordon’s 1962 Blue Note record Go! is

the kind of record that you can give to your friends who say they don’t

understand jazz and they will love it. Like Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, or Song for My Father by Horace Silver it crosses genre lines and

rises into classic territory. It has an energy and a quality to it that make it

special. It features Dexter Gordon on the saxophone, Billy Higgins on the

drums, Sonny Clark on piano, and Butch Warren on bass.

The

first track "Cheese

Cake" is a great example of some of the aspects that make this

session so special. Billy Higgins is an expert of propulsion, knowing exactly

when to switch between nudging with the hi-hat and snare into high gear with

the ride cymbal. Sonny Clark provides great harmonic support on the piano with

precise and short clustered chord voicings. When Sonny’s solo come around he

switches to a single note style that weaves in and out of the changes. Dexter

confidently plays the melody and the first solo displaying the sureness and

swagger that makes this this record famous. As if the first solo was not enough

after Sonny Clark takes his piano solo Dexter comes back for more. His ideas

are exact and followed thru logically. Throughout, his improvisations are

enabled by flawless technique and a bold tone. He seems to be creating and not

just striving to recreate a previous great performance, open to new ideas and

genuinely improvising at a master level.

In the

next song, "I

Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out To Dry," Dexter explores the sentiment

of a ballad without becoming sappy or flashy. The melody is straightforward and

heartfelt. Even during the improvisation the melody is never very far away. The

ballad seems to be an emotional vehicle, a way to convey feelings and mood rather

than a technical showcase. Butch Warren provides excellent harmonic support

while Billy Higgins showcases the lost art of drum brushwork. Once again Sonny

Clark gives great support for Mr. Gordon until he is called upon to briefly

solo over the bridge of the tune.

In the

next song, "I

Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out To Dry," Dexter explores the sentiment

of a ballad without becoming sappy or flashy. The melody is straightforward and

heartfelt. Even during the improvisation the melody is never very far away. The

ballad seems to be an emotional vehicle, a way to convey feelings and mood rather

than a technical showcase. Butch Warren provides excellent harmonic support

while Billy Higgins showcases the lost art of drum brushwork. Once again Sonny

Clark gives great support for Mr. Gordon until he is called upon to briefly

solo over the bridge of the tune.

"Second Balcony Jump"

is another midtempo number that starts out in a half time feel by the

rhythm section during the melody and then opens up to a 4/4 feel as the soloists

start to play. This provides an excellent springboard for the energy when

Dexter gets to his solo, moving from a laid back feel to a hard swinging

affair. Dexter is surely at his most impressive on this solo. He could be

blazing thru hard bop licks, laying on repeated note motifs, or inserting familiar

quotes (in this case “Mona Lisa”), and seem at home in his playing style. His solo

is followed up by Sonny Clark, and then he trades solo ideas with the able

Billy Higgins. The amazing thing about Higgins' drumming is how appropriate

everything is to the music. His technique is able, but never overtly flashy.

His choices always just feel correct for the music.

Higgins

opens the next tune "Love For Sale" with a punchy yet relaxed pseudo-Latin

feel. Sonny Clark provides a warm chordal bed for Dexter Gordon to play the

melody. The rhythm switches from Latin to straight ahead swing at the bridge

providing contrast and energy. In segues such as this you can hear the

singularity and purpose that infuses this session. All the transitions are

crisp and precise. The group is stylistically united and provides one of the

prime examples of what would become known as the Blue Note sound. Dexter plays

a blistering solo! He is followed by Sonny Clark on piano, and this is one of

his high points on the record as well. Butch Warren ventures his walking bass

lines into the higher register to compliment and intensify Clark's solo, while

Billy Higgins never fails to keep a steady sense of swing and bounce to the

song. That ride cymbal is pure magic, being the engine that that keeps the

entire train running.

Higgins

opens the next tune "Love For Sale" with a punchy yet relaxed pseudo-Latin

feel. Sonny Clark provides a warm chordal bed for Dexter Gordon to play the

melody. The rhythm switches from Latin to straight ahead swing at the bridge

providing contrast and energy. In segues such as this you can hear the

singularity and purpose that infuses this session. All the transitions are

crisp and precise. The group is stylistically united and provides one of the

prime examples of what would become known as the Blue Note sound. Dexter plays

a blistering solo! He is followed by Sonny Clark on piano, and this is one of

his high points on the record as well. Butch Warren ventures his walking bass

lines into the higher register to compliment and intensify Clark's solo, while

Billy Higgins never fails to keep a steady sense of swing and bounce to the

song. That ride cymbal is pure magic, being the engine that that keeps the

entire train running.

"Where Are You"

is a great interpretation of a jazz ballad. It is unadorned and pure without being

overly sweet or sentimental. The solos are relatively short and elegant. It is

on a song like this that a listener can hear the magic of the engineer Rudy Van

Gelder. Everything has its own sonic space and separation. You can hear the

definition and pitch of all the instruments, including the texture of the

drums, cymbals, and brushes. He is a fifth member of the band. Rudy Van Gelder

records the sounds and captures them on the record for Blue Note, defining the Blue

Note sound as much as any of their instrumental artists.

"Three O’Clock in the

Morning" starts off with the familiar piano introduction of "If I Were a Bell"

from Miles Davis’ arrangement recorded on the Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet record, but then gives way to

the song "Three

O’Clock in the Morning" - a clever bit of arranging to draw your

focus one way before having it redirected back to the material at hand. Once

again the rhythm section starts out in half time before perfectly stepping on

the gas in unison to support Dexter. The easy swinging solo allows the listener

to savor Dexter’s superb note choice and motivic development. Sonny Clark

follows with a blues-influenced solo that leads back to Dexter taking a brief

solo statement. This leads to the melody and the band plays the song out ending

on the "If I

Were a Bell" intro.

On the

record Go! all the stars are

aligning. Dexter and his band are at peak form, playing great songs while

informing and crafting a stylistic language. Dexter himself is technically

proficient but not playing so much that it is not musical or catchy, which has

always been a barrier to jazz for some. Finally you have one of the best

engineers of the century, Rudy Van Gelder, capturing the sounds for

preservation in an artful and distinctive manner that deserves its own

recognition, but that is for a different space. It all combines to make one the

best Blue Note classics and a record I Would Love To Turn You On to.

-

Doug Anderson

Monday, March 19, 2018

I'd Love to Turn You On #201 - Wayne Shorter - Juju

Looking at contemporary jazz saxophone I believe one can

trace the influences back to three saxophone players from the late fifties and

early sixties. Those players are John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Wayne

Shorter. John Coltrane studied and played with Ornette Coleman, as Wayne

Shorter studied with John Coltrane. It is amazing how they took each other into

consideration rather than trying to evolve inside a vacuum. Juju

is a glimpse of Wayne Shorter dealing with the evolving legacy of John

Coltrane’s impact upon jazz. As he was developing as an artist he had to

assimilate, process, and learn to mature with the musicians around him. The

result is one of his most powerful Blue Note releases, recorded in 1964 and

released in 1965. I chose Juju for I’d Love To Turn You On because I think it is a great portrait of an

artist as he is growing and evolving, reaching for that next step. This is what

makes Wayne Shorter such a vibrant player, from his days with Art Blakey

through his days with Miles Davis and up until today. He continues to make

relevant music, lending a rounded perspective that few can match.

Looking at contemporary jazz saxophone I believe one can

trace the influences back to three saxophone players from the late fifties and

early sixties. Those players are John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Wayne

Shorter. John Coltrane studied and played with Ornette Coleman, as Wayne

Shorter studied with John Coltrane. It is amazing how they took each other into

consideration rather than trying to evolve inside a vacuum. Juju

is a glimpse of Wayne Shorter dealing with the evolving legacy of John

Coltrane’s impact upon jazz. As he was developing as an artist he had to

assimilate, process, and learn to mature with the musicians around him. The

result is one of his most powerful Blue Note releases, recorded in 1964 and

released in 1965. I chose Juju for I’d Love To Turn You On because I think it is a great portrait of an

artist as he is growing and evolving, reaching for that next step. This is what

makes Wayne Shorter such a vibrant player, from his days with Art Blakey

through his days with Miles Davis and up until today. He continues to make

relevant music, lending a rounded perspective that few can match.

The band of McCoy Tyner on piano, Elvin Jones on drums, and Reggie Workman on double bass is two thirds of the classic Coltrane Quartet. Elvin Jones has a rolling and bubbling swing that interacts perfectly with Tyner’s bombastic chords on the first song “Juju,” laying a perfect bed for the melody. It is only after a few times through the harmonic structure that the frame of the tune, which is fairly simple and repetitive, becomes evident. This reveals the skill of the players, this ability to conceive of dense interlocking textures from simple source material and lay a cohesive bed that Shorter and McCoy Tyner can both solo in. Shorter’s solo seems patient to explore long tones at points, then work long phrases, and then hover on one note, not going any one place. It is the tone of the playing that makes the solo worthy of keeping; even if the solo is a little directionless the spirit of the playing has great zest. The spirit is in the exploration.

“Deluge,” the second tune, is a textbook Blue Note Swing. After the first somber statement by Shorter the entire band joins in for a cohesive, unstoppable demonstration of mid-sixties jazz. Elvin Jones in particular seems to be at the height of his powers, so relaxed that the drumsticks can just bounce on the snare or toms and do no wrong, while at the same time laying down a thick wall of impenetrable cymbals. Shorter then starts a solo with lengthy statements, taking his time working out his ideas and leaving time for the rhythm section to respond and fill space. The quarter note lock-up underneath Tyner’s solo between Reggie Workman and Jones’ ride cymbal is perfect, allowing Tyner to play single note fills or lay down big pedal point chords with his left hand and cascade massive fills with his right hand. The pocket on this tune is so great anything could happen.

“House of Jade” is a downtempo number that eventually picks up a little more speed. It has a ballad feel and the bridge, or middle part of the song, has a pedal point where the harmonic motion holds still in the rhythm section. This allows for increased activity on the melody instrument. It functions much the same way a zoom lens might, to bring greater detail to a certain part of a photo or frame in a picture or movie. The drums eventually double time under the sax solo propelling the rhythmic motion forward even when it drops back to the original time.

“Mahjong” starts with a playful drum solo and piano statement and then Shorter plays the melody which is supported by Tyner’s trademark quartal tones. Tyner is really the perfect piano player for these type of tunes because he can fill the space in songs that have two or three chordal areas in them and still make it interesting. As Tyner fills the space, Shorter plays the melody, and then this happens again. They play a bridge, restate the original melody and then repeat the whole thing. Tyner supplies a thick texture of harmony for his own solo that he can nestle in. While McCoy Tyner fills the space, it might be the opposite of what Shorter was experiencing in Miles Davis’ group where Herbie Hancock would boil a piano voicing down to one or two notes, a chord cluster, or lay out and let space and Tony Williams take over.

“Yes or No” is a real burner of a tune. The melody starts out with a flurry and ends with Shorter holding a long tone as Tyner, Workman, and Jones cruise below it banging out comping chords and flurries of color. This motif repeats several times before the bridge, in which Shorter plays out the song’s title in an up-and-down and back-and-forth manner. Jones’ ride cymbal is a constant North Star of precision during this song, one that all can look to as a guide in direction and meter. Shorter warms up on the first chorus but after that really opens up and plays his most technically demanding and passionate choruses of the record. Tyner takes over but takes a minute to regain the intensity of where Shorter left off, as if maybe he was not ready for Shorter to actually end his solo and was caught off guard having to begin his. A definite high point of the record. They end the record with “Twelve More Bars to Go,” a hard-swinging modified blues. Shorter really works the changes from inside to out. He is the only soloist and the band sounds great. In terms of innovation this has to be the most standard tune on the album. It doesn't have the passion of “Yes and No” or the catchiness of some of Shorter’s other tunes.

Juju was released in 1965 and recorded in 1964. Speak No Evil was released in 1966 and also recorded in late 1964. These are both great Wayne Shorter records. I think they are notable because they illustrate the process of one contemporary dealing with the legacy of another contemporary successfully. By this time John Coltrane was recording Crescent and A Love Supreme so he was continuing to innovate. Both of these artists are moving forward on their separate journeys. Shorter would have more Blue Note records and Miles Davis recordings, and then he would eventually become a founding member of Weather Report.

Hopefully I am turning you on to the fact that yes, Juju itself is great, but looking at it in context of Wayne Shorter’s evolution is the truly fun part. For me that has always been the amazing part of jazz records is how they link together, historically, via recording labels, or band personnel. Have fun listening!

-

Doug Anderson

Monday, January 8, 2018

I'd Love to Turn You On #196 - Miles Davis - Filles De Kilimanjaro

Filles

De Kilimanjaro and

In a Silent Way are two records that clearly lead away from

“traditional” jazz and into the “electric” jazz era for Miles Davis. The album

was released in 1969 and the title was a reference to a coffee company Miles

had invested in. Filles featured his quintet from the recordings

directly prior with two additional musicians. The musicians were Wayne Shorter

on saxophone, Tony Williams on drums, Ron Carter on electric rather than his

usual acoustic bass, and Herbie Hancock on Rhodes piano. The additional

musicians were Chick Corea, playing electric and acoustic pianos, and Dave

Holland, playing acoustic bass. Miles Davis was experimenting with taking away

the swing element in the music, at least from the rhythm section, and replacing

it with a more rock-based feel. Along with a transition in feel came a

transition in instrument choice. The horn section was using traditional horns,

but the rhythm section was altering their sound by using contemporary

instruments. Electric keyboards and basses start to appear where only acoustic

instruments had been before. Filles De Kilimanjaro is a snapshot of a

metamorphosis. It is a band in the midst of a change from one state to another,

and the record is a vital picture of the process.

Filles

De Kilimanjaro and

In a Silent Way are two records that clearly lead away from

“traditional” jazz and into the “electric” jazz era for Miles Davis. The album

was released in 1969 and the title was a reference to a coffee company Miles

had invested in. Filles featured his quintet from the recordings

directly prior with two additional musicians. The musicians were Wayne Shorter

on saxophone, Tony Williams on drums, Ron Carter on electric rather than his

usual acoustic bass, and Herbie Hancock on Rhodes piano. The additional

musicians were Chick Corea, playing electric and acoustic pianos, and Dave

Holland, playing acoustic bass. Miles Davis was experimenting with taking away

the swing element in the music, at least from the rhythm section, and replacing

it with a more rock-based feel. Along with a transition in feel came a

transition in instrument choice. The horn section was using traditional horns,

but the rhythm section was altering their sound by using contemporary

instruments. Electric keyboards and basses start to appear where only acoustic

instruments had been before. Filles De Kilimanjaro is a snapshot of a

metamorphosis. It is a band in the midst of a change from one state to another,

and the record is a vital picture of the process.

“Frelon Brun (Brown

Hornet)” is the first track and it starts with the alternate rhythm section of

Corea and Holland. The melody is played followed by a blistering solo by Miles,

in which Williams not only holds down the time, but takes interjection and

counter statement to a high level. Wayne Shorter does not ease up on the second

solo, nor does Williams. It is only on Corea’s solo that we get a little

respite and that may be only because the tone of his electric instrument would

not fully cut a combative Williams. After a bit of a back and forth from Corea and

Williams the melody is stated again and the song ends. Speculation that Davis

was inspired by James Brown and Hendrix certainly makes sense when examining

tracks such as these. A solid groove is laid down by Williams and Holland, but

then Corea and Williams have an ability to comment and interject in an

energetic fashion an additional layer on top of that first groove. This gives

the music a rhythm and a pulse of rock, a straight meter, but the added layers

and complexity of jazz.

“Tout De Suite” starts

on a cool slinky and downtempo groove, but quickly moves to Hancock prodding in

an increased tempo which sets up a new energetic space. Rather than set up a

steady groove, Carter uses his bass more as an accompanist with random prods

and Miles once again moves in with an aggressive first solo. Shorter takes the

second solo with Williams pulsating time on the high hat. Hancock and Williams

seem to have a real connection, while Carter seems tentative in his electric

duties, or maybe his nontraditional bass role. Hancock’s solo blends pulsation

with flurries and eventually melts slowly allowing for the head to melt back

in. Williams shifts the tempo back up after the head for a finale that fades

out. The liquidity of the transitions and the ease in which the ensemble flows

from one state of being to the next are remarkable. It is a level of

communication which only comes with playing music for an extended amount of

time and a willingness to explore. “Petits Machins (Little Stuff)” has a

playful head and continues in the theme of having a unison head. Ron Carter

fills more space by holding down pedal points and Tony Williams sets up space

filling it with a chattering snare. Miles once again takes the first solo and

the main theme is never too far away. Wayne Shorter’s solo is a little more

exploratory, allowing for more space in reply from Williams and Hancock. Tony

Williams is the glue on this track. You can hear the trust in space and the

patience. A less experienced band might have fallen apart. Herbie Hancock’s

solo is next and consists of right hand runs with occasional flurries of chord

clusters. It leaves Williams plenty of space to frolic. After Hancock’s solo

Miles comes back in with a short statement of the head out.

“Tout De Suite” starts

on a cool slinky and downtempo groove, but quickly moves to Hancock prodding in

an increased tempo which sets up a new energetic space. Rather than set up a

steady groove, Carter uses his bass more as an accompanist with random prods

and Miles once again moves in with an aggressive first solo. Shorter takes the

second solo with Williams pulsating time on the high hat. Hancock and Williams

seem to have a real connection, while Carter seems tentative in his electric

duties, or maybe his nontraditional bass role. Hancock’s solo blends pulsation

with flurries and eventually melts slowly allowing for the head to melt back

in. Williams shifts the tempo back up after the head for a finale that fades

out. The liquidity of the transitions and the ease in which the ensemble flows

from one state of being to the next are remarkable. It is a level of

communication which only comes with playing music for an extended amount of

time and a willingness to explore. “Petits Machins (Little Stuff)” has a

playful head and continues in the theme of having a unison head. Ron Carter

fills more space by holding down pedal points and Tony Williams sets up space

filling it with a chattering snare. Miles once again takes the first solo and

the main theme is never too far away. Wayne Shorter’s solo is a little more

exploratory, allowing for more space in reply from Williams and Hancock. Tony

Williams is the glue on this track. You can hear the trust in space and the

patience. A less experienced band might have fallen apart. Herbie Hancock’s

solo is next and consists of right hand runs with occasional flurries of chord

clusters. It leaves Williams plenty of space to frolic. After Hancock’s solo

Miles comes back in with a short statement of the head out. “Filles De Kilimanjaro”

has a unison head with an ostinato (or repeating line) that both the bass and

keyboard double. The melodic statement is played a couple of times and then Miles

takes a solo. The use of one key lets Miles use more extended tones to get

tense tonalities at the end of his solo. Shorter starts his solo with short

bursts of notes and balances it out with longer tones referencing the main

melody. The main melody is then broken up with only bits played and Hancock

soloing in between those statements. Miles solos a bit more still referencing

the main melody strongly, and then the track fades out. This track has the

sense of anticipation and mystery which is only resolved by Miles playing in a major

(happy) key. That major key (or happy resolution) gives the song a strong

resting place and a good ending. Chick Corea and Dave Holland are back for “Mademoiselle

Mabry (Miss Mabry).” This song is rumored to be a reworking of Jimi Hendrix’s “The

Wind Cries Mary.” The extended bass and keyboard blues statement with Williams

playing sparsely over the top is like nothing else on the record. Miles gently

plays the head with subtle inflections and half valve expressions. Williams

avoids any steady beat and just comments on the toms with an occasional high

hat snap or cymbal roll. Shorter opens up his tone a little for his solo,

allowing Williams to increase his interaction, while Corea and Holland state

the framework. Corea’s solo is largely a duet with Holland, with Williams just

hitting the form landmarks and a few cymbal flourishes. Miles then comes back

in to play briefly over the cycle that will signal the end of the song, and the

record. Compared to the rest of record “Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)” is

slowed down, simple, and starkly beautiful.

“Filles De Kilimanjaro”

has a unison head with an ostinato (or repeating line) that both the bass and

keyboard double. The melodic statement is played a couple of times and then Miles

takes a solo. The use of one key lets Miles use more extended tones to get

tense tonalities at the end of his solo. Shorter starts his solo with short

bursts of notes and balances it out with longer tones referencing the main

melody. The main melody is then broken up with only bits played and Hancock

soloing in between those statements. Miles solos a bit more still referencing

the main melody strongly, and then the track fades out. This track has the

sense of anticipation and mystery which is only resolved by Miles playing in a major

(happy) key. That major key (or happy resolution) gives the song a strong

resting place and a good ending. Chick Corea and Dave Holland are back for “Mademoiselle

Mabry (Miss Mabry).” This song is rumored to be a reworking of Jimi Hendrix’s “The

Wind Cries Mary.” The extended bass and keyboard blues statement with Williams

playing sparsely over the top is like nothing else on the record. Miles gently

plays the head with subtle inflections and half valve expressions. Williams

avoids any steady beat and just comments on the toms with an occasional high

hat snap or cymbal roll. Shorter opens up his tone a little for his solo,

allowing Williams to increase his interaction, while Corea and Holland state

the framework. Corea’s solo is largely a duet with Holland, with Williams just

hitting the form landmarks and a few cymbal flourishes. Miles then comes back

in to play briefly over the cycle that will signal the end of the song, and the

record. Compared to the rest of record “Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)” is

slowed down, simple, and starkly beautiful. Filles

is a

suite of music. As with many records the cumulative force of the whole is greater

than the individual force of its parts. The groundwork for In

A Silent Way was

being laid on this record, which is one of the fascinating things about Filles. The drums are more pattern-based, although Williams has the

ability to still hold a groove and interject. The bass is working with ostinato

patterns as opposed to walking lines. It repeats a rhythmic motif to add a

texture and a mood. All the songs are in one key lending to a subconscious

cohesiveness that might only be noticeable to a certain segment of listeners,

but gives a certain feel and sameness to the entire album, despite the

individuality of the compositions. We can see detail and individuality in each

piece, but only within the whole is the deeper meaning and contents revealed.

While a traditional head-solo-head format is being utilized, within that roles

are being exchanged and Miles’s new catchphrase “New Directions In Music” was

being put to the test. This is a catchphrase that his albums would bear from

now on. As we near the 49th anniversary of the record we have the

benefit of hindsight to show us what a masterpiece Filles

De Kilimanjaro is.

Miles always had remarkable taste in sideman. The personnel of this album is a

virtual who’s who of jazz legends today. Each of them lead their own ensembles

and expose great new talent to the jazz world. All are still with us with the exception

of Miles Davis and Tony Williams. Just following any one of these band members’

careers after this album will provide a trove of great listening. This was

always one of the greatest gifts of Miles Davis, starting from his days of bandleading

on the Prestige Label - choosing bandmates with interesting voices such as John

Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and Herbie Hancock, and so many more that made his

music so rich. So when people ask me which is my favorite, Filles

De Kilimanjaro or

In A Silent Way? I say why choose? Love them all, don’t leave any

out. I guess it depends which one you love that day, but I’d love to turn you

on to Filles.

Filles

is a

suite of music. As with many records the cumulative force of the whole is greater

than the individual force of its parts. The groundwork for In

A Silent Way was

being laid on this record, which is one of the fascinating things about Filles. The drums are more pattern-based, although Williams has the

ability to still hold a groove and interject. The bass is working with ostinato

patterns as opposed to walking lines. It repeats a rhythmic motif to add a

texture and a mood. All the songs are in one key lending to a subconscious

cohesiveness that might only be noticeable to a certain segment of listeners,

but gives a certain feel and sameness to the entire album, despite the

individuality of the compositions. We can see detail and individuality in each

piece, but only within the whole is the deeper meaning and contents revealed.

While a traditional head-solo-head format is being utilized, within that roles

are being exchanged and Miles’s new catchphrase “New Directions In Music” was

being put to the test. This is a catchphrase that his albums would bear from

now on. As we near the 49th anniversary of the record we have the

benefit of hindsight to show us what a masterpiece Filles

De Kilimanjaro is.

Miles always had remarkable taste in sideman. The personnel of this album is a

virtual who’s who of jazz legends today. Each of them lead their own ensembles

and expose great new talent to the jazz world. All are still with us with the exception

of Miles Davis and Tony Williams. Just following any one of these band members’

careers after this album will provide a trove of great listening. This was

always one of the greatest gifts of Miles Davis, starting from his days of bandleading

on the Prestige Label - choosing bandmates with interesting voices such as John

Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and Herbie Hancock, and so many more that made his

music so rich. So when people ask me which is my favorite, Filles

De Kilimanjaro or

In A Silent Way? I say why choose? Love them all, don’t leave any

out. I guess it depends which one you love that day, but I’d love to turn you

on to Filles.

-

Doug Anderson

Monday, March 6, 2017

I'd Love to Turn You On #174 - Nils Petter Molvaer – Khmer

Back in the 1990s, well before EDM made inroads

into mainstream popular culture, the European electronic music scene was

something that any musician with open ears was paying attention to. Rock and

pop musicians were (sometimes reluctantly) getting remixed by famous electronic

producers, DJs were becoming superstars, and so forth. So where better than

jazz, a syncretic genre that is always taking in influences from the entire

world of music, for this to take an early and lasting root? And who better than

Nils Petter Molvaer, a Norwegian trumpeter/multi-instrumentalist (he’s also

credited here with bass, sampler, treatments, guitar, and percussion) born in

1960, to cotton to the sounds his generation of European musicians were making

and find a way to make it blend seamlessly with his kind of jazz?

Back in the 1990s, well before EDM made inroads

into mainstream popular culture, the European electronic music scene was

something that any musician with open ears was paying attention to. Rock and

pop musicians were (sometimes reluctantly) getting remixed by famous electronic

producers, DJs were becoming superstars, and so forth. So where better than

jazz, a syncretic genre that is always taking in influences from the entire

world of music, for this to take an early and lasting root? And who better than

Nils Petter Molvaer, a Norwegian trumpeter/multi-instrumentalist (he’s also

credited here with bass, sampler, treatments, guitar, and percussion) born in

1960, to cotton to the sounds his generation of European musicians were making

and find a way to make it blend seamlessly with his kind of jazz? Of course the music is not without precedent.

It’s easy to point to Miles Davis’ similar groundbreaking experiments in the

1970s that fused jazz improvisation with popular rhythms to the consternation

of the jazz establishment, or the worldly ethno-ambient records that Jon

Hassell laid down in the 1980s (both with and without Brian Eno collaborating).

But Molvaer is doing something different - the rhythms are frequently based on the

then-contemporary dance beats of the drum & bass scene, but they're less

aggressive than what Miles essayed on an album like On the Corner, venturing frequently into ambient territory. And

where Miles played with a muscular assertiveness and Hassell drew on Middle

Eastern tonalities for his treated trumpet sounds, Molvaer is somewhere else

again, playing it cooler than Miles, with shorter phrases than the runs of the

Miles of the early 70s, but also playing around with the rhythm a lot, not as

much in the abstracted territory of sound that Hassell sometimes occupies. And

though maybe I’m putting too much into it by associating his cool middle

register tones and subtle phrasing with his Norwegian island upbringing, the

record often fits the image of a chilly Scandinavian landscape – but certainly

one where you can find Miles Davis albums to listen to.

Of course the music is not without precedent.

It’s easy to point to Miles Davis’ similar groundbreaking experiments in the

1970s that fused jazz improvisation with popular rhythms to the consternation

of the jazz establishment, or the worldly ethno-ambient records that Jon

Hassell laid down in the 1980s (both with and without Brian Eno collaborating).

But Molvaer is doing something different - the rhythms are frequently based on the

then-contemporary dance beats of the drum & bass scene, but they're less

aggressive than what Miles essayed on an album like On the Corner, venturing frequently into ambient territory. And

where Miles played with a muscular assertiveness and Hassell drew on Middle

Eastern tonalities for his treated trumpet sounds, Molvaer is somewhere else

again, playing it cooler than Miles, with shorter phrases than the runs of the

Miles of the early 70s, but also playing around with the rhythm a lot, not as

much in the abstracted territory of sound that Hassell sometimes occupies. And

though maybe I’m putting too much into it by associating his cool middle

register tones and subtle phrasing with his Norwegian island upbringing, the

record often fits the image of a chilly Scandinavian landscape – but certainly

one where you can find Miles Davis albums to listen to. The album kicks off with the title cut which

fades in slowly, leading with a melodic line from the guitar that is then

answered by Molvaer’s trumpet. A sampled bass thump plays in one channel while

a more acoustic-sounding bass (also sampled) interlocks with it in the other. Percussion

(performed live, not sampled) is light, fast, and skittering, right in the

wheelhouse of the drum & bass music of the time, playing it both fast and

slow simultaneously, though considerably less heavy than the real stuff. With

the rhythmic groundwork laid, Molvaer’s trumpet and Eivind Aarset’s guitar

trade solos mostly in a laid back, almost ambient mode until Molvaer starts

playing longer lines and using the higher register of the trumpet, at which

point it promptly fades into track two, “Tlon,” which starts mellow as well,

Molvaer’s trumpet cutting like a foghorn through the electronic blips and heavy

bass that surround it. Then guitar, trumpet, and an oddly perfect talkbox start

a dialogue before the beats kick in to very directly link this to the contemporary

electronic music world. But that’s before Morten Mølster’s treated guitar

creates a squalor that would derail the goodwill that had been generated by any

DJ playing this to a crowded dancefloor.

The album kicks off with the title cut which

fades in slowly, leading with a melodic line from the guitar that is then

answered by Molvaer’s trumpet. A sampled bass thump plays in one channel while

a more acoustic-sounding bass (also sampled) interlocks with it in the other. Percussion

(performed live, not sampled) is light, fast, and skittering, right in the

wheelhouse of the drum & bass music of the time, playing it both fast and

slow simultaneously, though considerably less heavy than the real stuff. With

the rhythmic groundwork laid, Molvaer’s trumpet and Eivind Aarset’s guitar

trade solos mostly in a laid back, almost ambient mode until Molvaer starts

playing longer lines and using the higher register of the trumpet, at which

point it promptly fades into track two, “Tlon,” which starts mellow as well,

Molvaer’s trumpet cutting like a foghorn through the electronic blips and heavy

bass that surround it. Then guitar, trumpet, and an oddly perfect talkbox start

a dialogue before the beats kick in to very directly link this to the contemporary

electronic music world. But that’s before Morten Mølster’s treated guitar

creates a squalor that would derail the goodwill that had been generated by any

DJ playing this to a crowded dancefloor. And so it continues, bouncing between more

contemplative numbers like “On Stream” with its trumpet, bass, and mellow

guitars over sampled percussion performing the most plainly lovely thing here,

and songs like “Access/Song of Sand 1” or “Platonic Years” which start out quietly

before rhythm starts to move to the fore and push the guitars and trumpet into

more rhythmically choppy waters to match. “Song of Sand 2” and “Exit” close

things out with the nosiest and quietest songs in the program, respectively.

And so it continues, bouncing between more

contemplative numbers like “On Stream” with its trumpet, bass, and mellow

guitars over sampled percussion performing the most plainly lovely thing here,

and songs like “Access/Song of Sand 1” or “Platonic Years” which start out quietly

before rhythm starts to move to the fore and push the guitars and trumpet into

more rhythmically choppy waters to match. “Song of Sand 2” and “Exit” close

things out with the nosiest and quietest songs in the program, respectively.

Taken as a whole, this is a

remarkable record, finding a way to take in haunting beauty, propulsive rhythm,

improvisation, and the experimental sound manipulations, and meld them into a

cohesive and entertaining whole. It’s something of a shock that it’s on the ECM

label, primarily known (especially then) for exquisitely recorded small group

chamber jazz, but good for them – it opened up the label to a new audience and

it broadened the label’s outlook on what they could release. Also be sure to

seek out Molvaer’s equally compelling second ECM album, Solid Ether, and then just start exploring – he has yet to put out

a record I haven’t enjoyed.

-

Patrick

Brown

Monday, August 22, 2016

I'd Love to Turn You On #161 - Sonny Sharrock - Ask The Ages

There is not much footage of Sonny Sharrock, but

what exists is revealing. If you go to Youtube and watch Sonny “Live at The

Knitting Factory from 1988” you get a pretty good idea what this amazing talent

was like. He appears on stage, a middle-aged, slightly portly, jovial

African-American gentleman cradling an electric guitar. His accompanists begin

a throbbing, jazzy beat and Sonny smiles and closes his eyes. He isn’t

particularly worried about playing a song, or structuring a solo. He is a bird

standing on a branch, waiting for the right triangulation of bait, breeze and

inspiration to lift him into flight. It happens and, eyes still closed, smile

switching to a grimace of concentration, he takes off. Sonny Sharrock’s solos

are not technical marvels, but rather highly emotional excursions into his

psyche. He claimed that he never really wanted to play guitar, rather that he

was a frustrated horn player chasing the elusive sound of his hero John

Coltrane. This schism is evident in his playing as he voices solos that are fat

and chordal in tone, but leap into wild single-note improvisational runs, much

as Coltrane did, especially in his final period. Sonny had a long history of

learning his style, starting in the 1960’s appearing on Pharoah Sanders Tauhid, and (legendarily) some

uncredited playing on Miles Davis’ guitar feast Tribute To Jack Johnson, then joining Herbie Mann’s groundbreaking

band for the latter’s strongest run of albums. He toiled in the jazz

underground in the 70’s releasing several amazing, avant-garde records, but

seemingly disappeared until bassist Bill Laswell tracked him down and mentored

him out of obscurity and into the spotlight where his reputation as one of the

most thrilling and unique voices in jazz increased until his untimely death

from heart failure in 1994.

There is not much footage of Sonny Sharrock, but

what exists is revealing. If you go to Youtube and watch Sonny “Live at The

Knitting Factory from 1988” you get a pretty good idea what this amazing talent

was like. He appears on stage, a middle-aged, slightly portly, jovial

African-American gentleman cradling an electric guitar. His accompanists begin

a throbbing, jazzy beat and Sonny smiles and closes his eyes. He isn’t

particularly worried about playing a song, or structuring a solo. He is a bird

standing on a branch, waiting for the right triangulation of bait, breeze and

inspiration to lift him into flight. It happens and, eyes still closed, smile

switching to a grimace of concentration, he takes off. Sonny Sharrock’s solos

are not technical marvels, but rather highly emotional excursions into his

psyche. He claimed that he never really wanted to play guitar, rather that he

was a frustrated horn player chasing the elusive sound of his hero John

Coltrane. This schism is evident in his playing as he voices solos that are fat

and chordal in tone, but leap into wild single-note improvisational runs, much

as Coltrane did, especially in his final period. Sonny had a long history of

learning his style, starting in the 1960’s appearing on Pharoah Sanders Tauhid, and (legendarily) some

uncredited playing on Miles Davis’ guitar feast Tribute To Jack Johnson, then joining Herbie Mann’s groundbreaking

band for the latter’s strongest run of albums. He toiled in the jazz

underground in the 70’s releasing several amazing, avant-garde records, but

seemingly disappeared until bassist Bill Laswell tracked him down and mentored

him out of obscurity and into the spotlight where his reputation as one of the

most thrilling and unique voices in jazz increased until his untimely death

from heart failure in 1994. Sharrock’s sound and catalog are not easy to get

your arms around. His early work on the Herbie Mann albums is hard to spot because

of the nature of his solos. One has to train their ear to listen for him,

because his early work tends to blend (self-consciously one would imagine) into

the overall framework of the songs. By the time of his difficult to obtain 70’s

solo work, he is fully immersed in avant-garde stylings and though those albums

contain some of his best playing, sometimes the music was too extreme for many

listeners. Once he came back in the 80’s he branched out in many directions (and

on many labels) including some heavy metal style playing with the band Machine

Gun. Like other enticing figures skirting the edges along jazz, rock,

avant-garde, and free-form, Sonny Sharrock is like a rare orchid: sightings are

seldom, but unforgettable.

Sharrock’s sound and catalog are not easy to get

your arms around. His early work on the Herbie Mann albums is hard to spot because

of the nature of his solos. One has to train their ear to listen for him,

because his early work tends to blend (self-consciously one would imagine) into

the overall framework of the songs. By the time of his difficult to obtain 70’s

solo work, he is fully immersed in avant-garde stylings and though those albums

contain some of his best playing, sometimes the music was too extreme for many

listeners. Once he came back in the 80’s he branched out in many directions (and

on many labels) including some heavy metal style playing with the band Machine

Gun. Like other enticing figures skirting the edges along jazz, rock,

avant-garde, and free-form, Sonny Sharrock is like a rare orchid: sightings are

seldom, but unforgettable. This difficulty in stylistically pinning him

down is what makes 1991’s Ask The Ages the

essential way “in” to Sonny Sharrock. It is a beautiful, hypnotic, intense album

that fulfills the promise of a guitar

player who plays his guitar like Coltrane played his sax. Produced by Bill

Laswell and Sonny himself, Ask The Ages reunites

Sharrock with Pharoah Sanders and throws jazz greats Elvin Jones (another

Coltrane alumnus) on drums and Charnett Moffett on bass into the mix. The

results are completely thrilling as Sanders and Sharrock take turns soloing in

a variety of sympathetic styles. Each of the 6 songs is a universe of complex

rhythm and spectacular soloing to discover. Sanders fills the role of Coltrane

well on some numbers like “Who Does She Hope To Be” but each song finds its

center within Sonny Sharrock’s completely un-copyable style of guitar playing. Take

the final number “Once Upon A Time” where he plays beautifully melodic single

lines over his own crunchy power-chording. It is a thrilling exercise in

musical freedom. It feels set loose from the bonds of genre, geography or

financial concern as the musicians bravely explore the outside of modern music.

This is something the label Axiom specialized

in, and we can thank Bill Laswell for creating a place for Sonny Sharrock and

many other groundbreaking musicians. Although it lasted less than a decade in its

original incarnation, Axiom was one

of the great labels of the modern era, and virtually everything they released

is worth hearing.

This difficulty in stylistically pinning him

down is what makes 1991’s Ask The Ages the

essential way “in” to Sonny Sharrock. It is a beautiful, hypnotic, intense album

that fulfills the promise of a guitar

player who plays his guitar like Coltrane played his sax. Produced by Bill

Laswell and Sonny himself, Ask The Ages reunites

Sharrock with Pharoah Sanders and throws jazz greats Elvin Jones (another

Coltrane alumnus) on drums and Charnett Moffett on bass into the mix. The

results are completely thrilling as Sanders and Sharrock take turns soloing in

a variety of sympathetic styles. Each of the 6 songs is a universe of complex

rhythm and spectacular soloing to discover. Sanders fills the role of Coltrane

well on some numbers like “Who Does She Hope To Be” but each song finds its

center within Sonny Sharrock’s completely un-copyable style of guitar playing. Take

the final number “Once Upon A Time” where he plays beautifully melodic single

lines over his own crunchy power-chording. It is a thrilling exercise in

musical freedom. It feels set loose from the bonds of genre, geography or

financial concern as the musicians bravely explore the outside of modern music.

This is something the label Axiom specialized

in, and we can thank Bill Laswell for creating a place for Sonny Sharrock and

many other groundbreaking musicians. Although it lasted less than a decade in its

original incarnation, Axiom was one

of the great labels of the modern era, and virtually everything they released

is worth hearing.

It’s really hard to compare Sonny Sharrock to

any other musician because of his utterly singular take on soloing, and his

lack of adherence to any “school” of jazz thought. He brings to his music the

same thrilling individuality and untrained freshness that Billie Holiday,

Charlie Parker or even Keith Moon brought. The excitement of finding an artist

so in love with their instrument and the idea of making music that even their

lack of training will not stop them is one of the fundamental reasons I listen

to music. It is the promise of human individuality and meaning given flesh.

-

Paul

Epstein

Monday, May 4, 2015

I'd Love to Turn You On #128 - Miles Davis - Agharta

The first sounds you hear on this

two-disc live set are notes from Miles’s Yamaha electric organ before they’re

joined by a dense, chugging, funky groove from the rest of the band until about

the 1:30 mark when Miles blasts the sound with a dissonant cluster of notes on

the organ. In this opening, a far cry from the delicacy of “So What,” the

textured beauty of the orchestral albums with Gil Evans or even the fractured

bop stylings of the second quintet, you get an immediate sense of what kind of

sound you can expect from this record. Even if you’ve been following his

notorious 1970’s electric period through to this point, this record still

provides something new and challenging compared to the murky strangeness of Bitches

Brew, the relentlessly nagging rhythms of On the Corner or the

muscular bravura of Live-Evil. I own every record Miles released in the

70’s and I like this one better than any named above – and almost any of his

albums of the electric era, period (though 1970’s Tribute to Jack Johnson

or 1969’s In A Silent Way might give me some pause). Miles changed

quickly at this time in his career and never looked back, so liking one record

gives you no guarantee that the next one will be to your tastes. And that first

couple minutes will let you know right away if this work is for you. It won’t

tell you everywhere it’s gonna take you on the ride, but you know from the

get-go that the protean Mr. Davis has changed his sound drastically yet again

here.

As always, what Miles is doing is

much more than just playing trumpet and writing or adapting musical themes – as

much as any bandleader in jazz, he’s utilizing the unique skills of his players

and “playing” the ensemble. So after he comes in and solos relatively quietly

through a wah-wah pedal for several minutes starting around the 2:30 mark –

hardly the delicate beauty of his 50’s solos or the robust open horn playing of

only a few years before – he hands the reins over to Sonny Fortune’s alto sax.

It’s something he’s unafraid to do throughout the record (and throughout his

career, actually) – allow other players to take the spotlight even knowing that

they may outshine him. And Fortune sounds great here, though after a bit Miles

decides that his solo is done by signaling with another blast from the organ

that tells Pete Cosey it’s time for his guitar to come in. Let’s talk about

Cosey for a minute.

As always, what Miles is doing is

much more than just playing trumpet and writing or adapting musical themes – as

much as any bandleader in jazz, he’s utilizing the unique skills of his players

and “playing” the ensemble. So after he comes in and solos relatively quietly

through a wah-wah pedal for several minutes starting around the 2:30 mark –

hardly the delicate beauty of his 50’s solos or the robust open horn playing of

only a few years before – he hands the reins over to Sonny Fortune’s alto sax.

It’s something he’s unafraid to do throughout the record (and throughout his

career, actually) – allow other players to take the spotlight even knowing that

they may outshine him. And Fortune sounds great here, though after a bit Miles

decides that his solo is done by signaling with another blast from the organ

that tells Pete Cosey it’s time for his guitar to come in. Let’s talk about

Cosey for a minute. Prior to joining Miles’s group in

1973, Pete Cosey was a session man at Chess Records, playing on records by

Fontella Bass, Howlin’ Wolf, Etta James, and Rotary Connection, among others.

But the only one that really gives an inkling of the music that would start

coming from his guitar under Miles’ tutelage is the much-maligned Muddy Waters

album Electric Mud, where the untamed noise he’d soon be issuing started

to peek its head out. Among Miles aficionados, the septet that Miles worked

with from 1973 until his temporary retirement in 1975 is often referred to in

shorthand as “the Pete Cosey Band” because of the prominence of Cosey’s

scouring guitar solos, compared in one stroke by jazz critic Greg Tate to both

Hendrix for his use of distortion and effects and Cecil Taylor for his harmonic

construction and the “out”-ness of his soloing.

Prior to joining Miles’s group in

1973, Pete Cosey was a session man at Chess Records, playing on records by

Fontella Bass, Howlin’ Wolf, Etta James, and Rotary Connection, among others.

But the only one that really gives an inkling of the music that would start

coming from his guitar under Miles’ tutelage is the much-maligned Muddy Waters

album Electric Mud, where the untamed noise he’d soon be issuing started

to peek its head out. Among Miles aficionados, the septet that Miles worked

with from 1973 until his temporary retirement in 1975 is often referred to in

shorthand as “the Pete Cosey Band” because of the prominence of Cosey’s

scouring guitar solos, compared in one stroke by jazz critic Greg Tate to both

Hendrix for his use of distortion and effects and Cecil Taylor for his harmonic

construction and the “out”-ness of his soloing.

So Fortune comes in and solos, but

not without Miles continuing to work with the rest of the group, shifting the

dynamics behind him and pulling the rest of the musicians out entirely at one

point, leaving Fortune solo in the truest sense of the word. And then Cosey

comes in and something else happens. The dense funk behind him is suddenly on

fire – if the electric sounds leading up to this point were operating at a

strong 100 volts, Cosey pushes it to 500 – probably not enough to kill you, but

enough to break the skin for sure. And his solo here is a marvel, a wild,

bluesy, psychedelic, noise-drenched beast with the band tightly wound

underneath him. Once his excoriating turn is done, a mellower groove kicks in,

with Davis’s prickly keyboards shining out through the ensemble before he picks

up his horn again.

After more of the lead cut, the

band moves into “Maiysha,” a piece that first appeared on the 1974 album Get

Up With It, and it lessens the intensity a touch as Fortune switches to

flute – but Cosey still rips into it with a solo even more “out” than the

freaky one he derails the studio version with. And even so, “Maiysha” provides

a beautiful, laid-back groove over which Miles takes a more lyrical solo than

on the previous track – before Cosey steps in, of course. The piece then tails

off towards texture and quiet near the end of the disc.

Disc two – a continuous medley of

music broken into two titles here – kicks off at a rocketing tempo with the

“Theme From Jack Johnson” (mislabeled as “Interlude”) and shortly works into a

Fortune alto solo. Percussionist Mtume is much more prominent here than the

first disc, especially when Miles is soloing. The two had a close musical

kinship and when Miles solos, it’s worth putting your attention toward how

sensitive and responsive Mtume is to Davis’s playing. The beat unexpectedly

changes to a shuffle behind a Cosey solo then cools down for Miles’ solo,

probably his best and most lyrical on the record, a reward for those who’ve

been waiting to hear him solo like this after so much sound and fury –

including much interaction with Mtume up in the mix. Miles ends his solo a

little after the 13-minute mark, when bassist Michael Henderson drops in the

bass riff from “So What” as Pete Cosey takes on a milder and also more lyrical

solo, proving that he’s not just a noisy effects man. “So What” is repeated

more obviously after the 17-minute mark before Fortune starts a flute solo and

the band moves into an eerie, slower part of the music full of jungle menace

and weird synth sounds. (I listened to it once at the Tropical Discovery exhibit

at the Denver Zoo and it was the perfect soundtrack!) As it gains rhythmic

force, they hit a new groove, and there’s a brief guitar solo that may be

rhythm guitarist Reggie Lucas (I haven’t been able to confirm this with any of

the Miles scholars I know, but I believe it to be true). Things cool back down

again for a textural interlude before a majestic, heavy, and melancholy Cosey

solo. This corresponds very closely to one Cosey plays in about the same spot

on Agharta’s companion piece Pangaea – Agharta documents

an afternoon concert, Pangaea was the evening show – and the Pangaea

solo is probably the best bit of Cosey’s work of all four discs (followed

closely by Agharta’s first disc one solo). The record mellows again

after that, with Miles on organ getting funky for a little bit a little after

the 44-minute mark until the band closes the whole thing on a mysterious fade

out with Cosey’s sparking feedback, Fortune’s floating flute, and Miles having

left the stage.

Disc two – a continuous medley of

music broken into two titles here – kicks off at a rocketing tempo with the

“Theme From Jack Johnson” (mislabeled as “Interlude”) and shortly works into a

Fortune alto solo. Percussionist Mtume is much more prominent here than the

first disc, especially when Miles is soloing. The two had a close musical

kinship and when Miles solos, it’s worth putting your attention toward how

sensitive and responsive Mtume is to Davis’s playing. The beat unexpectedly

changes to a shuffle behind a Cosey solo then cools down for Miles’ solo,

probably his best and most lyrical on the record, a reward for those who’ve

been waiting to hear him solo like this after so much sound and fury –

including much interaction with Mtume up in the mix. Miles ends his solo a

little after the 13-minute mark, when bassist Michael Henderson drops in the

bass riff from “So What” as Pete Cosey takes on a milder and also more lyrical

solo, proving that he’s not just a noisy effects man. “So What” is repeated

more obviously after the 17-minute mark before Fortune starts a flute solo and

the band moves into an eerie, slower part of the music full of jungle menace

and weird synth sounds. (I listened to it once at the Tropical Discovery exhibit

at the Denver Zoo and it was the perfect soundtrack!) As it gains rhythmic

force, they hit a new groove, and there’s a brief guitar solo that may be

rhythm guitarist Reggie Lucas (I haven’t been able to confirm this with any of

the Miles scholars I know, but I believe it to be true). Things cool back down

again for a textural interlude before a majestic, heavy, and melancholy Cosey

solo. This corresponds very closely to one Cosey plays in about the same spot

on Agharta’s companion piece Pangaea – Agharta documents

an afternoon concert, Pangaea was the evening show – and the Pangaea

solo is probably the best bit of Cosey’s work of all four discs (followed

closely by Agharta’s first disc one solo). The record mellows again

after that, with Miles on organ getting funky for a little bit a little after

the 44-minute mark until the band closes the whole thing on a mysterious fade

out with Cosey’s sparking feedback, Fortune’s floating flute, and Miles having

left the stage. I

understand those who don’t like this music – it’s too noisy for some, too

difficult to discern the structure of the long, loosely organized pieces for

others. Critics at the time mostly reacted badly to it as well, though it’s

gotten a reappraisal lately (even by some who initially trashed it) and is

rightly seen as a highlight in a career filled with many transcendent peaks.

But here’s the deal – it’s ensemble music, not necessarily soloist’s music,

despite my descriptions above of many great solos. It’s a dense weave of sound

that challenges the way we’re supposed to hear “jazz.” Is it even jazz at all?

Who cares!? If there’s a problem there, it’s with the word “jazz,” which isn’t

broad enough to contain music like this, not with the music herein.

I

understand those who don’t like this music – it’s too noisy for some, too

difficult to discern the structure of the long, loosely organized pieces for

others. Critics at the time mostly reacted badly to it as well, though it’s

gotten a reappraisal lately (even by some who initially trashed it) and is

rightly seen as a highlight in a career filled with many transcendent peaks.

But here’s the deal – it’s ensemble music, not necessarily soloist’s music,

despite my descriptions above of many great solos. It’s a dense weave of sound

that challenges the way we’re supposed to hear “jazz.” Is it even jazz at all?

Who cares!? If there’s a problem there, it’s with the word “jazz,” which isn’t

broad enough to contain music like this, not with the music herein.

- Patrick

Brown

Thursday, March 12, 2009

What Are You Listening to Lately (Part 12)?

King Sunny Ade – Juju Music

At first I didn't love this one the way I do now - subtler dynamics and a hook value somewhat lower than Ade and Martin Meissonier's subsequent outings for Island meant that it took longer to sink in. But after much acclimatization to Sunny Ade's catalog, it's easier to hear how this fits in as a particularly brilliant sampler of what he was doing around the time on his own before Meissonier put his hands in and added some Western touches to attune it more to the Euro-American sensibilities they hoped to hook into. Not too much though - this one's a good halfway point between the uncut Juju that brought Ade to fame and fortune in his native Nigeria and throughout Western Africa and the more pointedly Western stuff that failed to break him on a Marley-like scale Stateside and in Europe. All songs are good to great - more consistent than Synchro System if not quite as dynamic and about equal to the overall quality of much more Euro-African synthesis of the great and underrated Aura (though this one's way more Afro- than Euro-). "Ja Funmi" is one of the highest points I've heard in his catalog, kicking the album off right. And it never lets up afterward, even if the dense synthesizer forest of "Sunny Ti De Ariya" and the English lyrics of "365 Is My Number/The Message" are the only times afterward that it really makes major marks as standout tunes again. But it's high quality across the board, even if it sometimes - here's that subtlety again - doesn't exactly stand up and announce the differences in tracks. There isn't a part of this I don't enjoy at any time of day or night, especially when it's played loud (as it should be).

At first I didn't love this one the way I do now - subtler dynamics and a hook value somewhat lower than Ade and Martin Meissonier's subsequent outings for Island meant that it took longer to sink in. But after much acclimatization to Sunny Ade's catalog, it's easier to hear how this fits in as a particularly brilliant sampler of what he was doing around the time on his own before Meissonier put his hands in and added some Western touches to attune it more to the Euro-American sensibilities they hoped to hook into. Not too much though - this one's a good halfway point between the uncut Juju that brought Ade to fame and fortune in his native Nigeria and throughout Western Africa and the more pointedly Western stuff that failed to break him on a Marley-like scale Stateside and in Europe. All songs are good to great - more consistent than Synchro System if not quite as dynamic and about equal to the overall quality of much more Euro-African synthesis of the great and underrated Aura (though this one's way more Afro- than Euro-). "Ja Funmi" is one of the highest points I've heard in his catalog, kicking the album off right. And it never lets up afterward, even if the dense synthesizer forest of "Sunny Ti De Ariya" and the English lyrics of "365 Is My Number/The Message" are the only times afterward that it really makes major marks as standout tunes again. But it's high quality across the board, even if it sometimes - here's that subtlety again - doesn't exactly stand up and announce the differences in tracks. There isn't a part of this I don't enjoy at any time of day or night, especially when it's played loud (as it should be).

Miles Davis – The Musings of Miles

A really interesting and a unique, if not wholly exciting, item in the Miles catalog for a few reasons. First - it's from just before his triumphant return to public form at the Newport Festival in 1955 and shows him working at the peak of his 1950's style. Second - it's on the cusp of the formation of his First Quintet and has all the stylistic marks of that era of his development. Third - great song selection and pacing, starting with mid-tempo and ballad numbers then slowly speeding up over the course of the record and closing again with a nice ballad. Fourth, and most importantly - it's a quartet, just Miles and rhythm. There is nowhere else in his entire catalog where you get to hear him so nakedly and clearly without another horn drawing your interest away (especially since he had such a knack for picking really great players to work alongside him). But back to song selection a moment, where I'd like to point out his very interesting "A Night in Tunisia," in which Miles craftily dodges the part where every saxophone player has to take on "the famous alto break" if they're gonna tackle the song, and Miles just slyly makes it his own, giving a nod to Charlie Parker and then doing his own thing with it. As much as I enjoy the rest of the record, a good if not outstanding one in the catalog, this is the highlight. And it's that not-outstanding-ness of the rest of the record that keeps it hovering somewhere better than good, but not quite great. It's all well-done, it's all enjoyable, but only on "Tunisia" does it blindside you with surprises, even if I dig his Monk-answer "I Didn't" and other parts quite a bit.

A really interesting and a unique, if not wholly exciting, item in the Miles catalog for a few reasons. First - it's from just before his triumphant return to public form at the Newport Festival in 1955 and shows him working at the peak of his 1950's style. Second - it's on the cusp of the formation of his First Quintet and has all the stylistic marks of that era of his development. Third - great song selection and pacing, starting with mid-tempo and ballad numbers then slowly speeding up over the course of the record and closing again with a nice ballad. Fourth, and most importantly - it's a quartet, just Miles and rhythm. There is nowhere else in his entire catalog where you get to hear him so nakedly and clearly without another horn drawing your interest away (especially since he had such a knack for picking really great players to work alongside him). But back to song selection a moment, where I'd like to point out his very interesting "A Night in Tunisia," in which Miles craftily dodges the part where every saxophone player has to take on "the famous alto break" if they're gonna tackle the song, and Miles just slyly makes it his own, giving a nod to Charlie Parker and then doing his own thing with it. As much as I enjoy the rest of the record, a good if not outstanding one in the catalog, this is the highlight. And it's that not-outstanding-ness of the rest of the record that keeps it hovering somewhere better than good, but not quite great. It's all well-done, it's all enjoyable, but only on "Tunisia" does it blindside you with surprises, even if I dig his Monk-answer "I Didn't" and other parts quite a bit.

Funkadelic – Let’s Take It to the Stage

George Clinton and Co. are rarely perfect at album length. Their best ones always leave you a spot or two where you can run to the kitchen and get the snacks; where you'll skip to the next track; where you won't bother ripping some songs to your Ipod; and this one is no exception. That said, I enjoy it all even if not all equally. I count four great ones and six lesser ones, including the lengthy Bernie Worrell organ and synth workout with George's dirty mouth embedded deep down in the intro. But the overall mood is great; off the cuff nasty, funky, funny, soulful, rocking - everything you'd ask of these guys (and gals). And it's perhaps the best representation of their late-Westbound period; the point where they'd given up on the extended druggy drones of the early albums but had not yet achieved the slicker sound of their Warner Bros. years. It starts out great, hits another winner with the utterly un-P.C. "No Head No Backstage Pass," scores a classic to close the A with "Get Off Your Ass And Jam" and then opens the B with the almost Gothic-metal "Baby I Owe You Something Good." These four great ones are surrounded by fun, by funk, and by as solid an outing as they'd make under the name Funkadelic (and yes, I'm including Maggot Brain) or would make until One Nation Under A Groove. Pretty great, but not perfect - and isn't that more or less what you'd expect from George?

George Clinton and Co. are rarely perfect at album length. Their best ones always leave you a spot or two where you can run to the kitchen and get the snacks; where you'll skip to the next track; where you won't bother ripping some songs to your Ipod; and this one is no exception. That said, I enjoy it all even if not all equally. I count four great ones and six lesser ones, including the lengthy Bernie Worrell organ and synth workout with George's dirty mouth embedded deep down in the intro. But the overall mood is great; off the cuff nasty, funky, funny, soulful, rocking - everything you'd ask of these guys (and gals). And it's perhaps the best representation of their late-Westbound period; the point where they'd given up on the extended druggy drones of the early albums but had not yet achieved the slicker sound of their Warner Bros. years. It starts out great, hits another winner with the utterly un-P.C. "No Head No Backstage Pass," scores a classic to close the A with "Get Off Your Ass And Jam" and then opens the B with the almost Gothic-metal "Baby I Owe You Something Good." These four great ones are surrounded by fun, by funk, and by as solid an outing as they'd make under the name Funkadelic (and yes, I'm including Maggot Brain) or would make until One Nation Under A Groove. Pretty great, but not perfect - and isn't that more or less what you'd expect from George?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)